The day before his book, Freakonomics, was to be released, Stephen Dubner and I were playing Backgammon at our favorite diner on the Upper West Side and he was very upset. I thought he might cry. “I’m really scared,” he said. I was crushing him that day in the ongoing match we had begun in 2002 but I don’t think thats why he was scared. “This book might not do well. This is sort of my last shot. I might have to look for something else to do for a living if this doesn’t work out.” His first book, Turbulent Souls, was a hit, but his second book (and my favorite of his), Confessions of a Hero Worshipper, hadn’t done as well.

Stephen and I had met a few years earlier. When I was in the process of selling my old apartment (see What It Feels Like To Be Rich) a mutual friend of ours introduced us. Stephen was writing a book on the psychology of money at the time and he began following me around to get my story. He decided not to pursue that book (thankfully!) when Freakonomics came along but we became friends and began our regular backgammon match that continues to this day.

“You have nothing to worry about. This book is going to be a huge hit,” I said. I had read a galley, but to be honest, I had no idea. It seemed like a great book to me but what else was I going to say at that moment? (“Stephen, ummm, I hate to break it to you, but you might want to make sure you know how to use a mop if this book doesn’t pan out. Nothing wrong with that! But just don’t get your hopes up.”)

I didn’t hear from him for three or four days. Then he calls me and says, “look at our Amazon rank”. I went to Amazon top 100 page and figured I’d start at the top and work my way down. if I didnt see it in the top 100 I’d go to the book page where it would probably rank in the thousands somewhere. I started at the top. Ok, as expected, “Harry Potter” (one of them, I forget which) was number one. Then…number two – Freakonomics!

“Holy shit!”

“Yeah,” he said, “you were right. Its a hit.” And, of course, I didn’t admit then that I had just been saying that to be nice.

“Yeah, well,” I said, “anyone could tell it was going to be a hit. You were just nervous. But number 2! Holy shit!”

And it stayed at #2 for I think the next 150 weeks, give or take. Then Super Freakonomics was a hit, the blog is a hit, the documentary, now the radio show, etc.

So I spent a lot of time since then trying to figure out, what made Freakonomics a bestseller.

My first idea was that each chapter had an “A-ha!” moment. They showed a bunch of data, and then something unexpected would jump out of the data. This would drive discussions at cocktail parties, which would ultimately drive purchases of the book. So I tried this idea in my worst-selling book, The Forever Portfolio, but it didn’t work (I think less than a thousand copies sold, and I probably bought 900 of them). But when I read Super Freakonomics more of the pieces started to fall into place. I came up with four reasons why I think both books were runaway bestsellers.

- Secret Origins. When I was a kid I always liked the comics that told the secret origin stories of the heroes: Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, etc. I could read those over and over again. How did they turn from ordinary humans into such special beings. How could I turn from being an ordinary little kid into someone remarkable. In each chapter of the two Freakonomics books, Dubner and Levitt not only present the data but dive into whatever scientist that chapter created the data. What was his background, what were his motivations, what made his brain tick so that he needed to find out how to track down terrorist bank transactions, or study the incentives of chimps, or the motivations behind the global warming movement. Dubner is an expert at shadowing people around until he figures out what makes them tick (an excellent read is “Confessions of a Hero Worshipper” where he basically stalks his childhood hero, Franco Harris the football player, and tries to become his friend).

- Controversy. I don’t know why I missed this. But this is the obvious one. Almost every chapter has strong advocates for and against. A little anecdote. I was in San Diego driving around with super-newsletter econ guru John Mauldin (a staunch Texas Republican) and explaining the abortion chapter in Freakonomics (the book had just come out and he hadn’t read it yet). To say that it got him ruffled is an understatement. The first book had other controversial chapters: the chapter on how names are related to IQs, how drug dealers live with their mothers, etc. The second book kicked off right from the beginning with everyone arguing about global warming. Tons of blogs in every direction that, of course, fueled the sales fire. (as a side note, the only controversial book I had ever done, “Trade LIke a Hedge Fund”, sold well (for a hardcore trading book) only because the hedge fund manager I worked for at the time completely trashed it on his email list. More on that in another post).

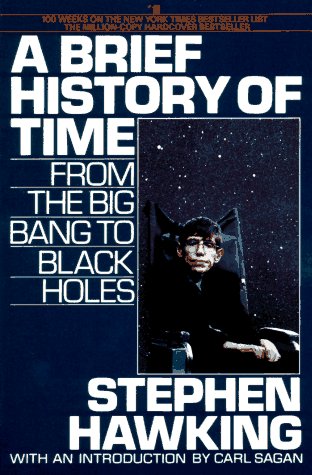

- Easy science. This can’t be underestimated. Every now and then I try to pick up a Stephen Hawking book or Amir Aczel book on popular physics or math but even with those guys the science is sometimes too complicated for me to follow (and I studied engineering and math in college and grad school). But Dubner and Levitt, two smart guys, really made an effort to make the science as easy as possible to understand. Anyone can read their chapters and make sense of (and, more importantly, appreciate) the science they are describing.

- The A-Ha moment! Yes, if you give monkeys money they will figure out prostitution! A-HA!

“I think you missed one,” Stephen said to me this morning over backgammon (he was trying to distract me since he had just doubled me). “Optimism”.

“I don’t get it. What do whore monkeys have to do with optimism?”

“There are entire industries out there that try to distort facts and statistics in order to make people afraid. Computer security, terrorism, global warming, etc. We try to take a step back and ask what are the real facts? Are these industries, that have incentives on their side to exaggerate, really giving us the correct solutions or are their better methods. For instance, have all the costs and increase in security procedures all over the planet been worth it? Have they actually saved lives? Throughout the books we take a look at these and at least ask the question, what happens if you step back a bit and really analyze these problems instead of jumping into knee-jerk solutions. With optimism people realize that their skepticism of all of the fear-mongers were justified.“

So there you have it. #5. Optimism.

I have a feeling, though, that even if I were to put these five elements together I still might not create a bestseller. But I don’t mind learning how to mop either.

Related posts:

Can a mutant douchebag change his life?

10 Things I Learned Trading for Victor Niederhoffer

(from the Freakonomics blog): James Altucher Strikes Again!